Combining apartments to create larger residential spaces is not a new concept, but it’s also not an everyday occurrence. Despite Mayor Bloomberg’s advancement of affordable pint sized micro units, the demand for large properties continues as does the practice of putting together multiple units. Even developers of new condo products are going back to their drawing boards to combine apartments to capture higher price yields per square foot. Given the current shortage of sizeable properties, one wonders whether we will be seeing more combinations.

Two purchasing scenarios exist for joining apartments. Buyer A buys the apartment of the neighbor(s) to the right, left, above and/or below the apartment he already owns to combine them. Buyer B buys two separate apartments to join them. Occasionally, buyers have the enviable opportunity to recombine apartments that had been separated previously (probably during the Great Depression) to restore them to their original footprint. Always, the procedure comes with challenges and often higher than typical maintenance fees. Done well, however, the process is definitely worth undertaking.

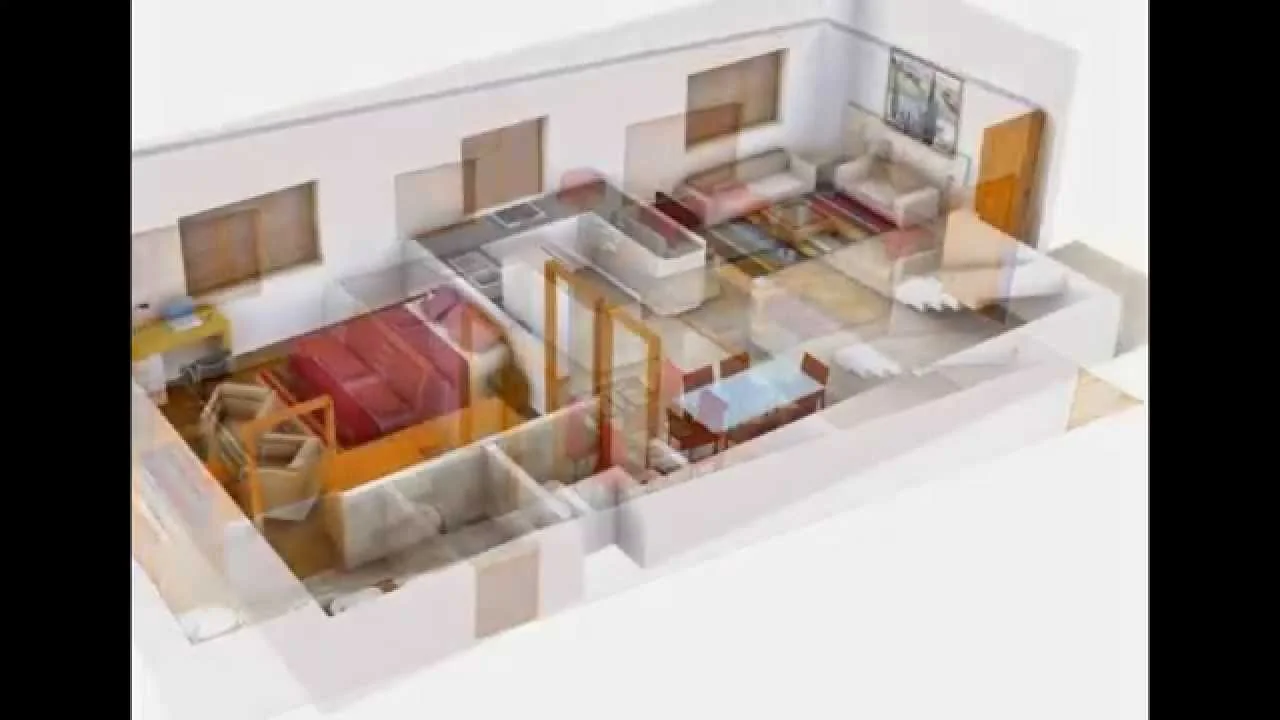

I’ve seen some fine examples of joined apartments where the combination is seamless, all the floors and baseboards have been redone, and the space flows gracefully in well laid out proportionate rooms. I’ve also seen disasters with mismatched floors and uneven ceiling heights, disconnected hallways and a patchwork of unrelated chambers. Not all contiguous apartments are worthy of being joined. The main problem with combinations, particularly in postwar buildings, is their tendency to stretch out horizontally so the result feels ‘railroady.’ It’s the wise homeowner who enlists the aid of a professional designer or architect upfront to determine whether combining will create a satisfactory end product.

Since November 1997, when the NYC Department of Buildings changed Building Code, the approval process for combining residential units has been streamlined. For combinations from 1968 to 1997, it was necessary to obtain an amended building Certificate of Occupancy because the combination reduced the total number of units. Today, the process is less arduous: the job can be self certified by a licensed architect after which the DOB issues a Letter of Completion to acknowledge the units have been combined legally.

“Whenever the opportunity arises,” says Attorney Neil Garfinkel of Abrams Garfinkel Margolis Bergson, “most owners, if they can afford it, will look to expand their residences.” Neil cites the example of a current client who slipped a note of inquiry under a neighbor’s door. In the contract Neil is preparing, he will acknowledge the buyer’s intention to combine the units, but won’t include a contingency that the co-op board approve the combination since the board must first approve the purchaser and only after that, the buyer will submit full architect’s drawings for board review.

Before entering into an agreement to purchase a “knock thru,” it’s critical to consult with a loan specialist to determine any special requirements. “It’s a greater risk to make a loan on two separate properties that are yet to be combined,” explains Melissa Cohn, EVP Manhattan Division of Guaranteed Rate. “If one apartment is already owned and the other is to be purchased, any existing loan will need to be refinanced so that the financing is secured against both apartments.” When two separate apartments are purchased, some banks will require borrowers to put money in escrow ($10,000 or .5% of the cost of the project, whichever is higher) which is released either upon completion or once the bank sees that the second kitchen has been removed.

With condominium apartments, the process is more complicated since condo units have separate tax lots. It’s best to consult with counsel to determine whether a new lot number from the Department of Finance is necessary for the newly created unit prior to filing the combination and whether amendments to the condominium declaration and offering plan are also required. If the units are not combined into one tax lot, a higher commercial tax rate may apply when the apartment is either financed or sold.

Attorney Craig L. Price of Belkin Burden Wenig & Goldman sees a problem when either the buyer or seller inherits an improperly filed preexisting combination. “Questions arise,” he explains, “about who will deal with the lack of certification.” He estimates it can take upwards of 6 months to remedy and as much as $10,000 to draw new plans and expedite DOB paperwork. “If this is not done,” he warns, “there will be problems with financing and closing up the road.”

Susan Zises Green, owner of the eponymous Susan Zises Green Inc. Interior Design, describes a recent Upper West Side project as “double the trouble, a third of the cost of purchasing new and triple the investment!” When an adjoining two bedroom apartment came up for sale next door to the owners of a three bedroom, Susan’s clients grabbed it. “It was easy to see how rooms could be repurposed,” she observes. “The second kitchen became an elaborate storage/laundry room. We were able to cordon off the second apartment where the contractors contained their work areas while the clients remained in their original home. They have since had offers extraordinarily above what it cost to buy and renovate.”

In real estate parlance, the whole is worth more than the sum of the individual parts. If you’re a two bedroom owner and thinking about selling, knock on your neighbor’s one bedroom door and call in an experienced real estate professional for advice on joining forces to present the possibility of a 7 room combination. If the opportunity arises, there’s clear economic advantage to doubling down in the current market.